To enlarge, click

on below image

(Shown standing at far left) Monsieur Sprimont,

World War I

To enlarge, click

on below image

Monsieur

Sprimont flying the route from Toulouse to Dakar for the French postal

service.

Monsieur

Sprimont flying the route from Toulouse to Dakar for the French postal

service.To enlarge, click

on below image

Celebration in Monsieur Sprimont’s little office classroom with his students on the occasion of his 90th birthday.

To enlarge, click

on below image

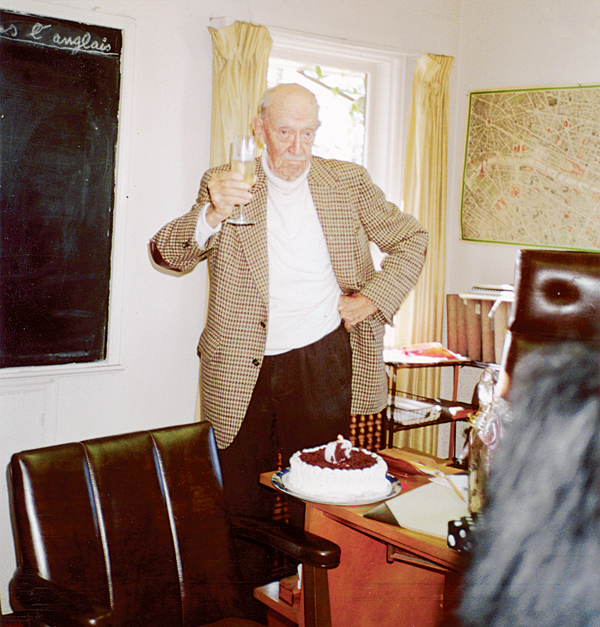

Monsieur Sprimont, his champagne and his 90th birthday cake.

People have a love-hate feeling for the French. We love their taste, their flair; but we hate it when they put us down. But there is a certain class of French who do not try to put us down and who have an unparalleled genuineness of character. I am thinking of people like honest French restaurateurs, who have no goal in life beyond preparing very special meals and running their little restaurants. When they become successful it never occurs to them to start up a chain of restaurants; they just keep doing the thing they know until eventually they decide to retire. Or the French menuisier, (carpenter) who learned his trade from his father and who is now in business with his son. His only goal is to continue doing his family work as a good, honest craftsman.

There are still quite a few French people like that and I have known a lot of them. But the one who touched my heart more than any other was Monsieur Sprimont. He was my French teacher for 25 years (and my Father Confessor!). I was with him when he died. I still think of him a lot and always with a little smile in my heart and a little choke in my throat.

Monsieur Sprimont was the adventurer of his day; he “did it all” as a young man. He was a French aviator in World War I. That was pretty close to the beginning of the age of military aviation. He flew reconnaissance missions over the German lines and did his part along with the United States and Britain in defeating Kaiser Wilhelm’s Germans. After the war Monsieur Sprimont piloted the little fabric winged planes of the French postal service. He flew the route from Toulouse, France to Dakar, Senegal, West Africa. It was a perilous route over the mountains of Spain and the waters of the Mediterranean.

One of his companion aviators was St. Supérey, who later became famous as the author of Le Petit Prince, among other books. He was lost at sea flying his little plane off the coast of southern France and never returned. Planes weren’t as safe then as they are now.

Monsieur Sprimont, mourning the loss of St. Supérey as well as a number of his other fellow aviators, made a deliberate decision to quit the flying service while he was still alive. So this tall, elegant, dashing young man gave up his flying to emigrate to America, to the university town of Palo Alto, California where I would meet him, and where he would spend the rest of his long life. New frontiers always interested Monsieur Sprimont; he kept up on the news about the astronauts and dreamed of someone making a mission to Mars. If this should ever happen in my lifetime I will be reminded of Monsieur Sprimont’s dream for mankind.

He married a nice French girl who stayed by him to the end, preparing the French cuisine he loved so much. After arriving in Palo Alto, he settled into a totally new career, the career of teaching French. He reasoned simply that French was a beautiful language (as he would say, une très belle langue) and that teaching French would be pleasurable and worthwhile. He rented a little second-floor room with large windows on three sides, windows that he could open to enjoy the pleasant Palo Alto climate and the fragrance of the flowers below. In this same room he conducted his mostly one-on-one French classes for the next 50 years.

Along with his teaching he spent the first several years writing his own textbooks, Volume One, a blue-covered paperback, and Volume Two, a red-covered one. As far as I know Monsieur Sprimont never wrote anything else; but he certainly did a great job on those books. “It is all in the book” as he would frequently say. “Turn to such and such a chapter and you will find your answer.”

Typically, I spent one hour a week studying French with Monsieur Sprimont. No matter how busy I was at work there was always time for that special hour of each week. How fun it was to read the little gems of French literature that he would uncover and to philosophize with him in French. The spicy stories of DeMaupassant, the detective stories of Simenon’s character, Inspector Maigret, the adventures of Monsieur Sprimont’s deceased pilot friend St. Supérey.

Incidentally, I learned more about the Catholic Church and the beauty of its teachings and traditions from Monsieur Sprimont than any other person. He had a strict church upbringing. I think his family wanted him to be a priest. For some reason, however, he renounced the church and became a Freemason. Even as he lay dying, he put no credence in the hereafter although he did seem to appreciate my wife’s praying for him. Over the years the lofty professor-student relationship grew into a personal friendship. We confided in one another; he helped me with my French correspondence, telling me what to say as well as how to say it. He taught my wife for many years and was perhaps the only one who really understood her. She was a charming lady and he liked to think of her as a daughter—he never had any children of his own. I recall when she lost the one invitation we had ever gotten from the Queen of England; I was all over her about that. Monsieur Sprimont said, “Perhaps she is doing the best she can.” Very prophetic words.

Monsieur Sprimont never asked material things from the world. He avoided the pursuit of money. Toward the end of his life he told me that he was paying for his choices; that inflation was driving up the cost of the tiny apartment where he and his wife lived and he could see his little savings dwindling away. The truth was that he never needed to worry since I was always ready to care for both him and his wife and always offered him to live in a little house we had.

His two biggest fears in life were senility and cancer. As a younger man he had smoked and he was realistic in knowing there was always a danger from that. To keep himself in shape he spent an hour each day walking all around the shopping center. He was a familiar figure—a tall, elegant, somewhat stooped, but colorful old man with his red French beret at a jaunty angle over his balding head.

Perhaps his biggest life crisis came at the age of 90 when he had to take a driving test to renew his driver’s license. If he had lost his license, he wouldn’t have been able to drive his little Volkswagen to work every day and he would have had to close his French school.

That little school was his life. He had made it completely self-sufficient; there was a giant French dictionary, a book case, a pencil sharpener on the wall, an audiocassette for recording and playing back students’ voices, and even a little sink for washing his hands. He shook hands with his favorite students (even embraced my wife) after our lessons. After shaking hands he always carefully washed his hands. Being scientifically trained he wanted to avoid germs that could cause him to miss his French classes. I never knew him to be ill.

At long last Monsieur Sprimont’s premonition became a terrible reality. He was diagnosed in the later stages of lung cancer. His last months were special for us all. He devoted all his remaining life and energy to his beloved classes. Each lesson was a treasure, but I couldn’t help crying after each class.

Then came the two weeks he missed his classes. My wife and I found him in his little apartment still rational. He stirred a bit and seemed so relieved to see us. He was slumped in his chair and motioned for me to lift him up a bit. As emaciated as he was I still realized I was lifting a big man, a great man.

When I had lifted him up he said to us, “I was hoping you would get here . . . I was waiting to see you . . . I wanted to say good-bye to you.” We embraced him and he sank into a coma for the last time.

Home

| Grandfather | Father |

Myself | Main Index

![]()